|

CANCER AWARENESS 101

Bringing cancer-prevention information to the Hmong,

a people whose native language has no word for cancer

|

|

| |

At his funeral, portraits of Aeng Chang look out over the shoulders of his widow, See Thao, and six

of their children |

|

|

At the Wat Tham Krabok refugee camp, a settlement of makeshift corrugated steel and bamboo huts

about 60 miles north of Bangkok, Aeng Chang fought his bladder cancer. He hired a shaman to perform a

soul-calling ceremony. A cow, buffalo and pig were sacrificed. Herbs, roots and tree leaves were tried.

The only treatment Chang rejected was radical cystectomy, the surgical removal of the bladder, recommended

by a medical doctor in a nearby town.

On June 16, after three years battling his illness and 25 in refugee camps, the former soldier arrived

in California. He, his wife, See Thao, and his eight children, ages 2 to 17, were the first of 15,000

Hmong refugees from Wat Tham Krabok granted permission to settle in the United States this year. Chang's

advanced cancer propelled his family to the front of the immigration line. The hope was that American

doctors might save his life.

Nine days after arriving in Sacramento, however, Chang died at UC

Davis Medical Center of inoperable, metastatic cancer of the bladder and rectum. He was 41.

Itís a tragedy Moon Chen doesnít want to see repeated. "The new Hmong immigrants have waited so long

and come so far, we want to arm them with the information they need to live long, healthy lives," says

Chen, co-leader of the Cancer Control and Prevention Program at UC Davis Cancer Center.

Unprecedented effort

Through a National Cancer Institute-funded project known as AANCART

— for Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research and Training — Chen is leading an

unprecedented effort to address the fears and traditional beliefs that prevent many Hmong from getting

regular cancer screenings, recognizing early cancer symptoms, and, when cancer occurs, undergoing effective

treatment.

Over the past two years, Chen and his colleagues have gathered a wealth of information about the cancer

incidence, risk factors and information needs of the Hmong, and mobilized one of the areaís largest Hmong

organizations, the Hmong Womenís Heritage

Association, to spread the word.

An unnecessary burden

"The cancer burden facing the Hmong and other Asian American communities is unique, unusual and unnecessary," Chen says. "Unique, because Asian Americans are the only racial group who experience cancer as the leading cause of death. Unusual, because the leading cancer killers of Asian Americans are infectious in nature. Unnecessary, because the risk factors for many of the cancers, such as those due to viruses or tobacco, are preventable."

Bladder cancer, for example, can be caused by a chronic parasitic disease, schistosomiasis, endemic in Southeast Asia. The Hmong also have high rates of liver cancer due to chronic hepatitis B infection.

Cervical cancer is prevalent as well. Pap smear rates are low, and the disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Hawaii to Harvard

|

|

| |

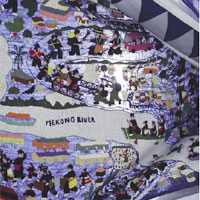

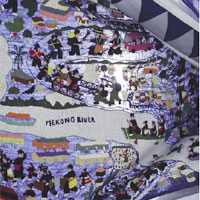

A Hmong embroidery depicts the flight from Laos to Thailand. |

|

|

UC Davis is headquarters for the $8.5 million AANCART program, which is made up of seven other institutions

across the country: Harvard, Columbia, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas, UCLA, UCSF,

University of Washington and University of Hawaii.

With AANCART funding, each institution focuses on a particular cancer in a particular Asian community.

In Seattle, for example, itís cervical cancer in Cambodian women. In Los Angeles, itís breast cancer in

Japanese American women.

In Sacramento, the focus is on basic cancer awareness in the Hmong, with an emphasis on cancers caused

by preventable infections, particularly liver cancer caused by chronic hepatitis B infection.

Californiaís Hmong

California is home to at least 65,000 Hmong, most of whom arrived as refugees in the late 1970s and 1980s,

driven from their homeland by the Pathet Lao after the United States withdrew from the Vietnam War. Of

the new wave of Hmong immigrants, an estimated 4,000 are expected to settle in Sacramento, which has the

nationís third-largest concentration of Hmong after Fresno and St. Paul, Minn.

For the newest Hmong immigrants, AANCARTís focus is on eliminating infectious causes of cancer, primarily

through hepatitis B immunization. For the Hmong who have been in the United States for a decade or more,

the focus is on preserving the communityís low rates of lung, colon and breast cancer through education

about the risks of such Western behaviors as smoking, a high-fat diet and a sedentary lifestyle.

Cancer basics

A course called "Cancer Awareness 101" is the centerpiece of AANCARTís Hmong outreach. It is

designed to give members of the Hmong community, particularly the elders and shamen who often serve as

medical decision makers for their families, the same baseline cancer knowledge that more mainstream Americans

grow up knowing: Excess sun exposure can cause skin cancer. Regular Pap tests prevent deaths from cervical

cancer. Smoking causes lung cancer. Breast self-exams can detect tumors while they are small and easier

to treat. Itís a straightforward idea, but the first all-day Cancer Awareness 101 course, offered at a

hotel conference room on the Medical Center

campus in the spring of 2003, encountered unanticipated complexities.

Reginald Ho, a past president of the American Cancer

Society, served as instructor for the pilot course. He quickly realized how few Western medical terms

have counterparts in the Hmong tongue.

Whatís a cell?

The word "cell" alone took 20 minutes to communicate. Hoís Hmong translator chose the Hmong

word nqaj, meaning "the smallest thing," a controversial choice. Some in the audience,

fluent in both Hmong and English, preferred noob, meaning "seed." Others made a case

for adopting the English word, cell. Similar debate ensued over translation of the many internal organs

that have no name in Hmong.

|

|

In traditional Hmong culture, it is believed that illness occurs when the soul wanders from the body.

Shamen, like Kang Thao, help call the soul home |

|

|

|

At the end of the day, UC Davis medical students of Hmong ancestry agreed to prepare Hmong-language versions

of the course.

With AANCART support, the Hmong Womenís Heritage Association went on to translate three National Cancer

Institute guides dealing with liver, skin and cervical cancer into the two predominant Hmong dialects,

White Hmong and Green Hmong. Dao Moua, cancer program coordinator at the Hmong Womenís Heritage Association,

now teaches the course in both English and Hmong.

A second course, Cancer Awareness 201, was designed to teach Hmong-English medical interpreters the vocabulary

and concepts they need to effectively translate conversations about cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis

and treatment.

Building trust

|

|

| |

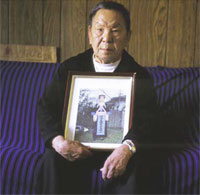

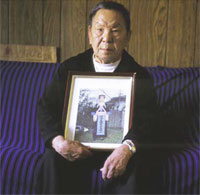

Chong Yia Xiong of Stockton displays a photo of his late wife, Chou Vang, who died of cancer. UC Davis

offers Hmong-speaking "navigators" to help families through cancer treatment |

|

|

The two courses have been offered to more than 200 members of the Hmong community over the past year,

with plans for further classes. "Participants have told us they want more cancer courses offered to the

Hmong community," Moua says. "There is a need to address such concerns as treatment side effects, lack

of knowledge about cancer, language barriers, lack of trust between patients and providers and misuse

of medication."

Through AANCART, Moua has developed an orientation program for new Hmong arrivals to Sacramento. Families

receive free health kits, hepatitis B information and "What is Cancer?" brochures in Hmong. She has established

a Cancer Support Network that provides Hmong patients at UC

Davis Cancer Center with a Hmong-speaking "navigator" who can accompany them to medical appointments,

provide interpreting and translation services, and act as advocates when needed. Working with AANCART

investigators at UCLA, Moua has also conducted focus group research to assess the diet and exercise habits

of Californiaís Hmong.

Empowering community organizations like the Hmong Womenís Heritage Association is central to the AANCART

approach.

"When we engage community-based organizations to aid their own, train their own and perform research

to help their own, we see the power of their commitment to their own," says Kenneth Chu, chief of the

NCIís Disparities Research Branch. "This is the secret to their success."

Three-day funeral

Aeng Changís three-day funeral was held over the July 4 weekend at a Veterans of Foreign Wars hall in

South Sacramento. Local Hmong radio stations reported on the death of the first immigrant from Wat Tham

Krabok and announced his long wake. Outside the hall, stacks of 50-pound rice bags, brought by mourners

as gifts to the family, flanked the entrance doors. Inside, Changís clansmen beat drums and played the

qeej, a traditional bamboo flute. From a kitchen inside the hall, women prepared rice, vegetables

and meat for family and guests.

"Itís very tragic," a cousin said, standing next to a photo of Aeng Chang. "He never even got to see

the apartment where his wife and children will live. But we are a large clan, and we will make sure his

family is taken care of."

AANCART will be there, too, to help ensure Changís children, and others in the new generation, grow up

with the information they need to protect themselves from the leading killer of Asian Americans.

|