|

SOY POWER

The soybean, cultured with shiitake mushrooms, may

slow prostate cancer

|

|

| |

Soy beans may help fight prostate cancer |

|

|

Faced with a choice of surgery, radiation, doing nothing or taking a daily handful of soy-mushroom

capsules to treat his early prostate cancer, Clair Bishop went with the nutritional supplement. The retired

insurance company executive is part of a study to determine if the capsules can indeed control early,

localized prostate cancer.

"It'd be great if it works," says Bishop, 75, an avid golfer and tennis player living in Placerville.

"I've never been in the hospital a day in my life, and never taken any medicine. I'd rather keep it that

way, if I can. And I'm definitely more comfortable doing something than doing nothing."

Bishop is a volunteer in a UC Davis Cancer

Center study of the efficacy of an extract cultured from soybeans and shiitake mushrooms. Known as

genistein combined polysaccharide, or GCP, the extract has shown promise as a way to slow or halt prostate

cancer progression in men with early, untreated disease.

It's not a cure, and it's unknown how long its therapeutic effects might last. But GCP could enable men

like Bishop to postpone the day they'll need aggressive medical treatment.

Watchful waiting

Many men with low-grade prostate cancer decide against surgery or radiation, treatments that can result

in impotence or incontinence. But the conservative alternative, often called "active surveillance"

or "watchful waiting," can be tough psychologically. Ralph deVere White, professor and chair

of urology and principal investigator of the study, says a new option like GCP could help ease that

anxiety, enabling more men to stay a conservative course and avoid the significant risks of surgery or

radiation.

"It's a promising approach," deVere White says. "If we can find a chemopreventive agent capable of slowing

or stopping the progression of early, localized prostate cancer, it would be an important development

in our treatment of the disease."

Long used in Asia

GCP is used as a complementary therapy for prostate cancer in Japan, Korea and other parts of Asia. UC

Davis has been studying the extract in the laboratory for many years, with unrestricted support from a

Japanese company that makes the supplement.

|

|

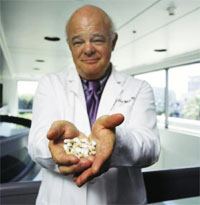

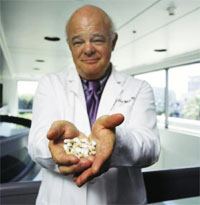

| Professor Ralph deVere White |

|

|

|

The first clinical study, a small phase I trial involving 13 prostate cancer patients, took place at

the Cancer Center two years ago. Results

of the study appeared in the Journal of Urology last year.

In the study, deVere White found that the supplement reduced PSAs by as much as 61 percent in the prostate

cancer patients who had received no previous treatment for their disease. For unknown reasons, GCP didn't

benefit men who had received radiation, surgery or hormone therapy. The only side effect was diarrhea.

Phase II trial begins

The new trial, a phase II study, ultimately will enroll 64 men. The volunteers will receive either GCP

or a placebo for six months. Neither the patients nor the study investigators will know who is taking

the placebo until the six months are over.

At that point, patients who received the placebo, along with patients who received GCP but had minimal

change in their PSAs, will be offered a six-month supply of the supplement at no cost. When that second

six-month period is up, all patients who continue to show a decreased or stable PSA may continue receiving

GCP for free, as long as they have their PSAs checked every six months.

If the results are promising, deVere White will seek National

Cancer Institute funding for a much larger phase III study.

Nature's pharmacy

GCP wouldn't be the first cancer therapy to come from natural sources. According to the American

Cancer Society, a third of new cancer therapies reaching the market today are derived from natural

substances. To earn FDA approval, all of the agents first demonstrated safety and effectiveness through

rigorous laboratory and clinical testing.

Taxol is probably the best-known example. Derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree, taxol was subjected

to four decades of scientific investigation and clinical trials before earning FDA approval and becoming

widely available in 1994.

Because of the double-blind nature of the GCP study, Bishop won't know for several months whether the

capsules he's been taking contain GCP or a placebo. Nevertheless, he seized the chance to participate.

"I did a lot of research, and got several medical opinions," he says. "I thought this

was definitely worth a try."

|