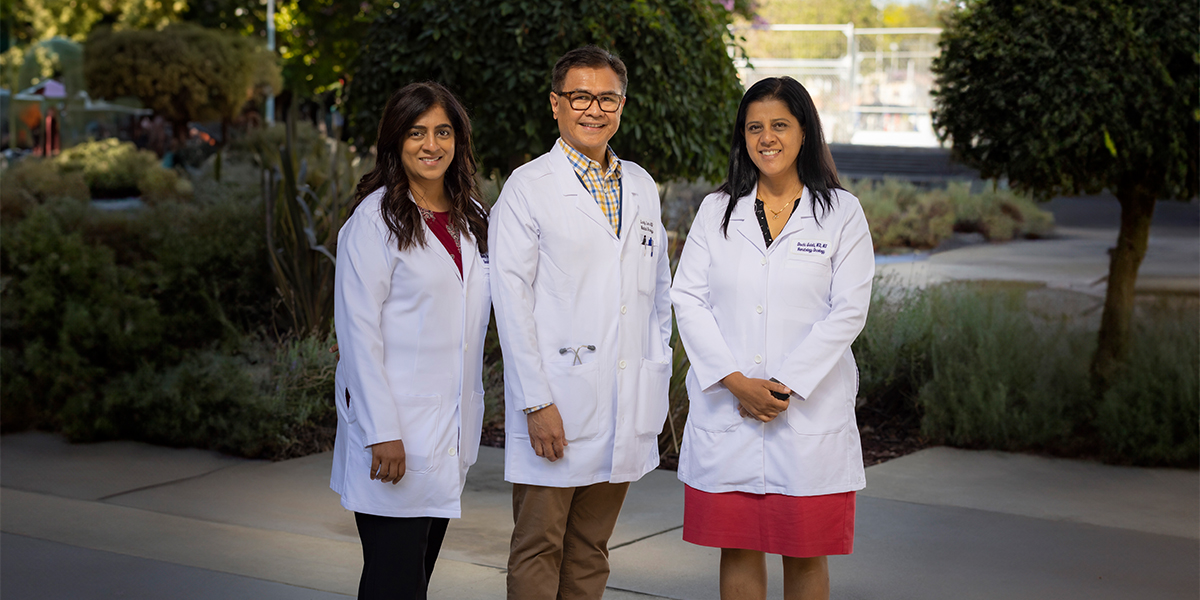

Cancer center Director Primo “Lucky” Lara Jr. was a key investigator of the SWOG Cancer Research Network clinical trial known as the EVEREST study. The goal was to see if the anti-cancer drug everolimus helped people with kidney cancer following surgery. Similar therapies are already used to improve the outcomes of patients with breast, colon, and lung cancer.

Results from the clinical trial showed that many kidney cancer patients who took the drug, including those at high risk of relapse, remained alive longer after they underwent surgery to remove the cancer. The findings were published in The Lancet, one of the world’s highest-impact academic journals.

Patients from UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center and nearly 400 other U.S. cancer centers were enrolled in the study. Over a 54-week period, participants received 10 milligrams daily of oral everolimus or a placebo.

“Improvement was seen primarily in patients with very high-risk disease, while patients with intermediate high-risk disease saw no improvement,” Lara said. “This encouraging observation warrants further study. We must continue our work to discover and test new agents to improve outcomes in people with kidney cancer.”

Everolimus is among a class of drugs known as mTOR inhibitors, which block the growth of cancerous cells.

The EVEREST trial enrolled 1,545 patients who were diagnosed with intermediate high-risk or very high-risk renal cell carcinoma (cancer in the lining of the tubes of the kidney). All previously had undergone surgical partial or complete nephrectomy — removal of their cancerous kidney.

“Recurrence of cancer in these patients ranges from 2% to 40% following surgery,” Lara said. “It is important to test active new agents as part of clinical trials after their surgery and before their cancer returns and spreads.”

Multiple purpose research

The large, high-impact SWOG trial provided a rich body of research for Shuchi Gulati, an assistant professor of hematology and oncology at UC Davis. She was able to explore a type of kidney or renal cancer that is seldom studied because it is not as common.

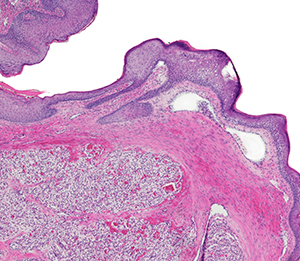

Most forms of renal cancer are either clear cell or non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) — so-called because of their appearance under a microscope. The National Cancer Institute reports that about 80% of kidney cancer cases nationwide are attributable to clear cell RCC.

“Consequently, most clinical trials focus on patients with clear cell histology, and unfortunately patients with more rare forms of kidney cancer tend to be left out,” Gulati said. “There is a signal that everolimus might benefit patients with chromophobe RCC that forms in the cells lining the small tubules in the kidney. We were not able to definitively support that based on this analysis, probably because of the small number of patients in these subgroups. But combining results from numerous studies could potentially lead to meaningful results.”

That prospect motivates Gulati to continue her work.

“We know that the standard treatments that work for clear cell RCC, like immunotherapy and targeted therapy, don’t work for the rare types of kidney cancer,” Gulati said. “The impetus now should be to focus on these smaller subsets of non-clear cell RCC, to start finding not only what doesn’t work but rather what does work.”