Addressing diarrhea in pediatric kidney transplant patients

Nephrologists must walk a tightrope between maintaining adequate immunosuppression and preventing infection

Diarrhea is an occasional, and uncomfortable, fact of life. For most people, it clears in a day or two, and they can go on with their normal lives. But for kids who have just received a kidney transplant, diarrhea can be a life-threatening condition.

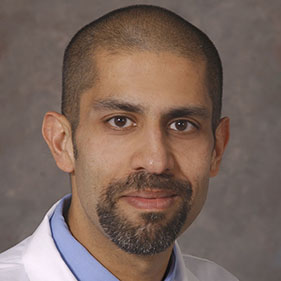

A paper published in the journal Pediatric Nephrology details how diarrhea can impact pediatric transplant patients and offers potential clinical responses. Lavjay Butani, chief of the Division of Pediatric Nephrology and Machi Kaneko McBee, assistant professor of Clinical Pediatrics, are co-authors of the paper.

“Pediatric nephrology at UC Davis has been developing protocols to standardize care for our transplant patients, including for diarrhea,” McBee said. “Unfortunately, when we did the literature search, we couldn’t find much. We felt it was important to get this information out there because it has a direct impact on patients’ health and well-being.”

A complex problem

Pediatric kidney transplant patients face many challenges, particularly in the first couple of years. They are taking powerful immunosuppressant drugs to prevent organ rejection, making them prone to infection. Even a relatively mild cold could warrant a trip to the emergency room.

Diarrhea might indicate that a patient has an infection, possibly a serious one, such as C. difficile. On the other hand, it is also a well-known side effect of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), a commonly used immunosuppressant. To compound the problem, patients — particularly young ones — may not be eager to report on their bowel movements.

In addition, there are no diagnostic tests that can show whether mycophenolate is causing diarrhea. When treating diarrhea, clinicians can — and often do — decrease the MMF dose, but that increases the risk of rejection.

“Post-transplant management is really a balance between finding the right immunosuppression dosage to prevent rejection while protecting patients from infection,” McBee said. “Preventing both is always a seesaw.”

A nuanced response

McBee notes that it’s critically important to get this right. Diarrhea can cause dehydration and kidney injury but it can also affect how medications are absorbed, leading to high and even toxic blood levels. Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressive drug that is metabolized in the intestinal lining before entering the blood. Diarrhea inflames that lining, leading to incomplete metabolism and possible tacrolimus toxicity.

The guidelines in the paper encourage pediatric nephrologists to thoroughly investigate the causes before taking action. That could mean taking additional patient history, ordering more laboratory tests or pursuing other diagnostic strategies. Ultimately, clinicians should make every effort to rule out treatable infections before zeroing in on MMF as the potential culprit.

“The evidence is clear that we should not be reflexively reducing mycophenolate,” McBee said. “There may be other causes we need to address, allowing us to maintain appropriate MMF doses. If the diarrhea does not get better, then we can look at adjusting the patient’s immunosuppressive medications.”

Rather than reducing the immunosuppressive drug doses, we believe nephrologists should consider probiotic or antimotility agents. This approach offers an alternative way to manage diarrhea without increasing the risk of rejection.” —Lavjay Butani

A multidisciplinary approach

Butani and McBee encourage nephrologists to work closely with other specialties, particularly infectious diseases. There are emerging medicines for C. difficile and other dangerous pathogens that could make this process easier for patients.

“Unless we involve our infectious disease colleagues, we may not even know about some of these new treatments,” Butani said. “We want to encourage nephrologists to more closely track emerging infectious disease medications and consider using them.”

The authors would also like their colleagues to explore other anti-diarrheal approaches, including probiotics and antimotility agents, which reduce the number of bowel movements. While there have been concerns these medications could harm immunosuppressed patients, Butani and McBee have found little data to support that.

“Rather than reducing the immunosuppressive drug doses, we believe nephrologists should consider probiotic or antimotility agents,” Butani said. “This approach offers an alternative way to manage diarrhea without increasing the risk of rejection.”