Local teen walks again after tubing accident, thanks to UC Davis Children’s Hospital

Julia Lynn was a talented gymnast. She had just taken first place at a regional gymnastics competition and her future looked bright. On a day out with friends in June 2022, that future changed dramatically when Julia went out water tubing, an activity where participants ride an inner tube pulled behind a boat by a tow rope.

The fun outing at Shasta Lake turned scary when two tubes being pulled behind the same boat collided. One tube landed on the other, trapping the 15-year-old. When the tubes hit another wake, Julia was freed but was thrown into the water. The accident left her without feeling on the left side of her body.

“At first, I didn't really realize I was hurt. But then my arm got super swollen,” Julia said. “It turned blue and got really cold. I knew that was not normal.”

Water tubing has grown in popularity, and so have related accidents. According to a 19-year study published by the Center for Injury Research and Policy, the annual number of water tubing-related injuries increased 250 percent over the study period, rising from 2,068 injuries in 1991 to 7,216 injuries in 2009.

“Boating, swimming and water sports are some of our favorite ways to cool off and have fun in Northern California,” said Jennifer Rubin, injury prevention specialist at the UC Davis Health Injury and Violence Prevention Program. “We talk to families about preventing drowning by wearing life jackets and emphasize that boating and alcohol don’t mix. But we might forget to talk about other injuries associated with water sports.”

Symptoms worsen

When she arrived at the local hospital near her home in Cottonwood, in Shasta County, Julia couldn’t feel anything as doctors poked her. No response to the hot and cold test either. Julia’s mom Melissa Lynn recalls the doctor saying it might be a spinal cord injury.

“I thought it was a pinched nerve or something,” Melissa recalled. “I wasn't expecting that.”

The next thing the Lynns knew, Julia was being transported to UC Davis Children’s Hospital for critical care. This was possible thanks to patient-centered partnerships with more than two dozen hospitals across Northern California, as UC Davis Health works to improve access to care across the region.

“I flew in a helicopter to the airport and by the time we boarded the plane to Sacramento, I had no feeling in my leg at all,” Julia said.

When Julia arrived at the UC Davis Pediatric Emergency Department, she remembers being told to lay completely still. Doctors ran tests, including X-rays and more detailed MRI and CT scans.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive medical imaging test that produces detailed images, including the organs, bones, muscles and blood vessels. CT scans — short for computerized tomography — combine a series of X-ray images taken from different angles of the body and use computer processing to create cross-sectional images (slices) of the bones, blood vessels and soft tissues.

“It was a whirlwind,” Melissa remembers. “Just seeing her lying there was traumatizing. We didn’t have any answers.”

An uncertain future

Julia was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). A percutaneous central catheter was placed to administer medication. Results revealed that Julia had an incomplete spinal cord injury, as well as neurological brain function disorder.

“Julia presented to our hospital after a hyperextension injury to her neck with symptoms of weakness and numbness to the left side of her body,” said Allan Martin, associate program director of neurosurgery at UC Davis Health. “CT scans showed no fractures, and the brain and cervical spine MRI did not show a clear injury or a cervical ligament sprain.”

“The way it was described to us what that it was kind of like a concussion to the spine,” Melissa said. “We were told that nothing was severed, but Julia’s brain had basically shut off the pathways to the left side of her body.”

An incomplete spinal cord injury leaves the patient able to transmit some messages to or from the brain. People like Julia with incomplete injuries retain some sensory function. Similarly, neurological brain function disorder means the brain is unable to send and receive signals properly and there is a disconnection in the function of the lobes. Processing of sensations also can be affected.

The worst part for me was when Julia tried to stand and couldn’t. Julia was a competitive gymnast and had just won first at regionals. You take this girl who is so incredibly active and athletic and now, she can't stand on her own. I had to leave the room.” —Melissa Lynn, Julia's mom

“I couldn't move my arm up or wiggle my fingers when I tried,” Julia said. “My brain would not transfer thoughts. It was scary.”

“The worst part for me was when Julia tried to stand and couldn’t. That was very hard,” Melissa said. “Julia was a competitive gymnast and had just won first at regionals. You take this girl who is so incredibly active and athletic and now, she can't stand on her own. I had to leave the room.”

Hope for Julia

Doctors determined no surgery was required, but months of rehabilitation lay ahead. The prognosis? No one could be sure what would happen — injuries like this can take up to five years to heal — but the Lynns and the team at UC Davis Children’s Hospital knew they were going to do everything they could to get Julia on her feet again.

“Once physical and occupational therapy began, I felt like we were doing something positive and productive,” Melissa Lynn said. “It was a little bit easier because we had a purpose; we had something to work toward.”

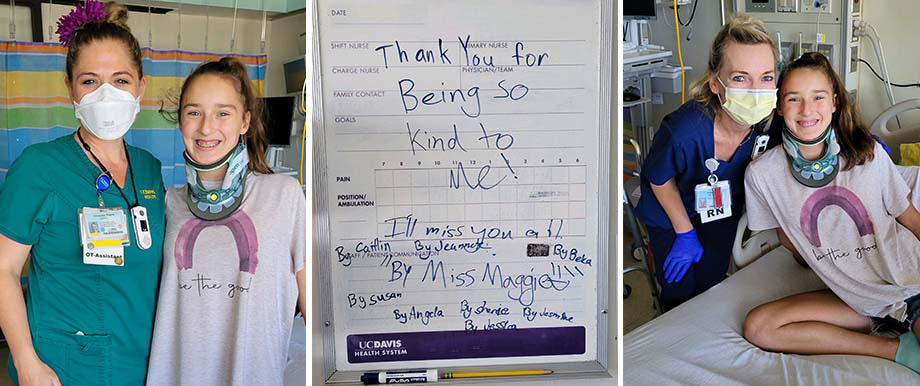

“Julia put great effort into all the daily tasks we had her partake in during therapy,” said occupational therapist Angela Ziegler. “She made daily progress, which was great to see.”

Julia’s month-long stay at the hospital was filled with exercises designed to help her regain her strength, punctuated with zooming the hallways in her wheelchair and visits from creative arts therapists and facility dog, Daniels, and his handler.

“Daniels was able to support Julia multiple times throughout her stay, helping her cope with the ups and downs of a lengthy hospitalization,” said Kristen Cady, facility dog handler and child life specialist. “As she worked toward her goals during occupational therapy and physical therapy, we helped her celebrate accomplishments.”

“We worked on getting dressed, with an emphasis on her upper extremity strength and balance while standing,” Ziegler said. “Julia was able to translate that strength to tie her shoes and tie her hair up into a ponytail. By the end of rehab, she was pretty independent.”

Although rehabilitation was hard and painful, Julia and her family took comfort in the care provided by the staff and the relationships they built.

“We spent so much time there, we really got to know the staff. Everybody was friendly and did the best they could to make us comfortable,” Melissa said. “They involved me in Julia’s care. I felt a part of everything. You could tell they really wanted to see her be successful. It was awesome.”

When discharge day arrived on July 8, 2022, Julia walked out of the hospital and into her future. She continued with outpatient physical therapy for a year, graduating in June 2023, just in time for her 16th birthday. Although things look different now — she’s riding horses rather than doing gymnastics — Julia’s outlook is as positive as the day she was admitted.

“She’s a glass half full kind of kid,” Melissa said. “I am sure that helped with her recovery.”

What else helped? Treatment at UC Davis Children’s Hospital.

“The team really focused on Julia, helping her get better,” Melissa said. “They made us feel at home. It was as good an experience as you can have in the hospital.”