Virtual reality exam checks eye health and screens for early signs of Alzheimer’s

UC Davis researchers are using virtual reality technology to make eye exams easier for seniors and to investigate its potential for spotting brain changes before symptoms appear

An audio-described version of this video is available here.

In the recreation room at Eskaton Village in Carmichael, Bonnie Dale, one of the residents, is trying on a virtual reality (VR) headset.

Colorful exercise balls of different sizes line one wall, and behind Dale is a rack with equally colorful arm weights. Just outside the room, residents swim laps in the facility’s pool.

A trained operator helps Dale put the device on her head and then places a controller in her hand to help her navigate the device’s program. Dale practices pressing the trigger with her finger and then gets started.

The operator tracks her progress on a tablet.

Although it looks like Dale is playing a game, the VR platform is checking her eyesight.

A virtual assistant, “Annie,” gives Dale instructions as she clicks her way through the program, which tests things like visual acuity, the ability to see different colors and shapes and how her pupils react to light.

The entire eye exam takes Dale about fifteen minutes. The results are displayed on the tablet and can be automatically transmitted to her ophthalmologist.

Dale, a retired health care consultant, is a patient and supporter of the UC Davis Eye Center.

“Being able to have the tests done, absent being at the Eye Center, but having the results go right to the doctor, is wonderful for the aging community. It’s a wonderful, wonderful gift,” Dale said.

Eyes can reveal brain changes

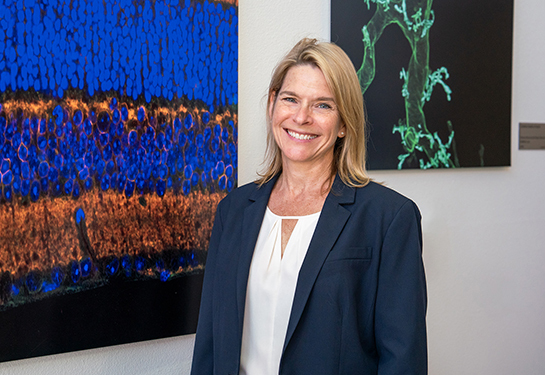

The eye testing at Eskaton Village is part of a pilot program designed by Yin Allison Liu. Liu is a neuro-ophthalmologist at the UC Davis Eye Center who also holds appointments in the departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery.

Liu wants to bring virtual eye exams to the community. She’s also trying to find out if a research program like hers could help identify neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, before people even experience symptoms.

“Recently, research has found that visual processing changes occur about 10 to 12 years before a formal diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Liu says. “Most people don’t realize this, but the eye is part of the central nervous system. We can see vision changes through different types of ophthalmic testing, which will reflect brain changes.”

Last year, Liu and her colleagues at the Eye Center published a review paper documenting changes in the eye, specifically the retina, the thin layer of cells at the back of the eye, observed in patients with mild cognitive impairment. The condition sometimes precedes Alzheimer’s disease.

Liu explains that the virtual reality platform, Olleyes, does not diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or any neurological conditions.

“But it helps us screen for vision conditions or visual changes that can indicate cognitive dysfunction and therefore provide information about the overall brain health,” Liu says. “This way, we have another angle at the diagnosis or even early detection of the disease.”

The ultimate goal is to make early detection accessible for everyone, so that their eye and brain conditions can be detected and addressed before major issues occur."—Yin Allison Liu, Associate Professor of Ophthalmology, Neurology, and Neurosurgery

Virtual reality eye exams may eventually screen for neurologic diseases

The device Dale used at Eskaton is one of two models from Olleyes, which was co-founded by neuro-ophthalmologist Alberto Gonzalez-Garcia.

The idea behind the virtual reality device is to make eye care more accessible and efficient using artificial intelligence and virtual reality technology.

Gonzalez-Garcia trained as a doctor in his native Cuba, specializing in neuro-ophthalmology.

In 2007, he studied glaucoma during a fellowship at UC San Diego. In 2018, he co-founded Olleyes, which is based in Summit, New Jersey.

The company collaborates with university researchers like Liu, who use the virtual reality eye device in their research.

Some studies have looked at using the device for eye exams in emergency departments and free health clinics. Others have used it to make pediatric eye exams more like a fun video game.

Liu is among the first researchers to use the VR platform to look for changes in vision and responses to commands that might indicate neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Olleyes helped customize the program for Liu’s pilot study, allowing her to note issues like hearing problems alongside visual decline, or if participants struggled to follow the virtual assistant’s simple instructions, all of which could be linked to cognitive changes.

Gonzalez-Garcia hopes to one day integrate a cognitive testing module into the device, but most of the tests validated through years of study, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), are proprietary.

Cognitive tests are often done with a piece of paper or sometimes a tablet. MoCA asks test participants to name various animals (lion, rhinoceros, camel), draw a clock, and recall a list of words given early in the assessment. A trained health care professional administers the test.

But Gonzalez-Garcia notes that a virtual test may eventually be preferred. All the functions that require a pencil can be done with a controller. “Another significant advantage is that the instructions would be delivered in a standardized way by an AI virtual assistant, ensuring a consistent evaluation experience for all test takers,” Gonzalez-Garcia said.

The need for Alzheimer’s testing is expected to rise significantly.

An estimated 6.7 million older adults have Alzheimer's disease in the United States. By 2060, that number is expected to nearly double, to 14 million.

Liu’s goal with her pilot program is to find scalable ways to increase the chance for early detection of cognitive diseases. By bringing the program to a senior community at an assisted living facility, where residents may find it harder to attend an in-person eye exam, she hopes to make detecting vision changes and cognition-related visual dysfunction even easier.

“Early diagnosis or early detection will give us the power to make lifestyle modifications or open the doors to clinical trials or new treatments,” Liu said. “The ultimate goal is to make early detection accessible for everyone, so that their eye and brain conditions can be detected and addressed before major issues occur.”