UC Davis medical students move to Modesto to provide care, improve health equity

REACH pathway launches year-long clinical training experience with Kaiser Permanente

The UC Davis School of Medicine is transforming health care for the Central Valley.

A group of seven students has relocated to Modesto for an entire school year as part of a new initiative to bring better health to a region that is medically underserved, short on doctors and struggling with health disparities.

The students care for patients at hospitals and outpatient clinics under the direction of Kaiser Permanente physicians who are also committed to improving health equity. The Central Valley clinical experience, a new requirement of the REACH pathway, happens during the third year of medical school, a time when most students are serving at hospitals in Sacramento.

REACH stands for Reimagining Education to Advance Central California Health.

“It makes a big difference to put students back in their community for their clinical training,” said Alicia González-Flores, a UC Davis Health internal medicine physician who moved to the Central Valley from Mexico as a teenager and now leads the medical school’s pathway initiatives.

The students also have roots in the Central Valley – and are thus eager to practice medicine there.

“This program allows our students to continue making connections and strengthening the community bonds that will motivate them to go back and practice medicine in the San Joaquin Valley,” González-Flores added.

This academic year marks the first in which a cohort of UC Davis students live and train entirely in the Modesto area.

It makes a big difference to put students back in their community for their clinical training… This program allows our students to continue making connections and strengthening the community bonds that will motivate them to go back and practice medicine in the San Joaquin Valley.”—Alicia González-Flores, executive director, Community Health Scholars, UC Davis School of Medicine

Training near the neighborhood where he was raised

Benjamin Vincent, a REACH student, likes to peer through the large windows on the fourth floor of Kaiser Permanente Modesto Medical Center to spot the neighborhood where he and his two brothers were raised. The house is just across Highway 99 in Salida, a Stanislaus County community of about 14,000 people and bountiful almond orchards.

“It still, at its core, has a small-town feel,” Vincent said. “If you ever watched Cheers, it’s an everybody-knows-your-name type of place.”

Now he’s back living at the home in his old upstairs bedroom, down the hallway from his parents’ bedroom, with his wife Jacqueline who is six months pregnant with their first child.

Vincent can’t wait to return to the area permanently. “To be able to come back home and do what I’m passionate about with people in our community, it’s just very, very fulfilling and seems like a calling,” he said.

During his first two years of medical school, Vincent attended lectures and laboratory science classes, and lived near the UC Davis Health campus in Sacramento.

Now he spends full days at the Modesto hospital. Under the guidance of a Kaiser Permanente physician preceptor, he cares for patients in a different clinical area every six weeks in a role similar to that of a resident physician.

One of the highlights is bonding with patients, which is easier when the provider is from the area and can relate to anything from local politics to traffic tangles.

Studies show that patients who have positive, trusting relationships with their primary care providers tend to have better health outcomes.

In rural areas, however, many new doctors don’t stick around. Instead they move to larger cities with better salaries to pay down their student loans.

Vincent, who moved to Salida in May, tells of a patient during his family medicine rotation who asked the aspiring doctor, “So, where are you going to go after this?”

Vincent’s response: “Well, I was born here, and hopefully I get to come back.”

The answer prompted the patient to smile enthusiastically.

Vincent was touched, too, as he heard himself speak about his future career. “I was grinning from ear to ear,” he said. “You know, it kind of sent chills down my spine because not many people get to have a dream and have it become a reality.”

There’s value in being a local doctor, Vincent said.

“To know that there’s not only just a patient, but an entire community that really believes in you, and wants you there, and is happy to have you there, that really just means a lot.”

A solution to the Central Valley’s provider shortage

A long-established goal of the UC Davis School of Medicine is to train physicians for practice in diverse communities where they are most needed to bridge California’s health equity gap.

The San Joaquin Valley, from about Lodi to Bakersfield, has faced a physician shortage for decades, in part because there’s no medical school in the region, despite efforts to open one at UC Merced. Research shows that most doctors start their careers in or near the area where they trained as residents.

However, there’s also a lack of residency programs in the Central Valley. UC Davis uses REACH to expose medical students to community-based clinical experiences early in their education.

It wasn’t the medical school’s first foray into medical education in the center of the state.

In 2011, UC Davis, in partnership with UC Merced and UC San Francisco, launched San Joaquin Valley (SJV)-PRIME, a pathway for students hoping to practice medicine in the valley. The program educated students in Sacramento, then moved them to Fresno for their final two clinical years, resulting in greater numbers of UC Davis graduates returning to pursue residency training and practice in the region.

But in 2018, the UC Regents decided to transfer SJV-PRIME to UCSF, which prompted UC Davis to start REACH that same year.

The highlight of REACH is the partnership between UC Davis School of Medicine and Kaiser Permanente. It provides the students robust clinical experience within the largest integrated health system in California, which lately has focused greater attention on reaching underserved communities.

Kaiser Permanente’s Central Valley Service Area includes Modesto Medical Center, Manteca Medical Center, and medical offices within Stanislaus and San Joaquin counties.

By introducing students to its hospitals and clinics, Kaiser Permanente also sets itself up as a potential workplace for the students once they graduate and complete their residencies.

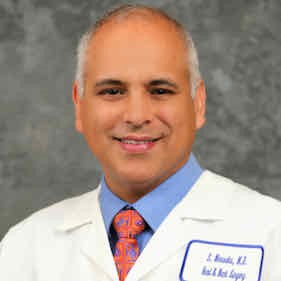

“It's very clear that UC Davis has an exceptional reputation for developing amazing physicians and learners,” said Sanjay Marwaha, the physician-in-chief for Kaiser Permanente Central Valley. “We wanted to partner with this incredible organization to help develop future physicians, consistent with UC Davis and Kaiser Permanente’s focus on improving the health and welfare of the communities in which we serve.”

The valley, Marwaha said, has approximately 45 physicians to every 100,000 residents, while the Bay Area’s average physician-to-patient ratio is nearly 70 to 100,000. “Those numbers are staggering, and they haven’t changed probably in about 20 years,” he said. “We have a lot of work to do to build up our health care workforce here in the San Joaquin Valley, in the Central Valley.”

The partnership, he said, brings tremendous benefits to both UC Davis and Kaiser Permanente.

“It’s actually a two-way street where we can provide medical knowledge, information and teaching, and expose them to a vast array of pathology which they may not see in their home institution.”

Drawing students who are already connected to the area also helps them to develop relationships with patients. “They understand the community, they know the community,” Marwaha said. “So here they have an opportunity to give back to their families and friends and loved ones.”

It's very clear that UC Davis has an exceptional reputation for developing amazing physicians and learners… We wanted to partner with this incredible organization to help develop future physicians, consistent with UC Davis and Kaiser Permanente’s focus on improving the health and welfare of the communities in which we serve.”—Sanjay Marwaha, physician-in-chief, Kaiser Permanente Central Valley Area.

A student eager to break down barriers to care

Najiba Afzal, a REACH student who immigrated with her family to Manteca from Afghanistan when she was five, has personal experience with the health equity gap. Her parents lacked English fluency and didn’t have much rapport with their doctors.

She often had to translate for her Pashto-speaking parents at their medical appointments, which made her feel awkward.

Afzal graduated from Stanislaus State University in Turlock.

She initially encountered resistance from men in her family when she expressed interest in becoming a physician – because it’s more culturally acceptable to be a stay-home wife and mother, she said.

But she now looks forward to a medical career near her hometown to serve the growing population of Afghan refugees facing challenges with the new language, culture and access to quality care.

“I can be that person to help somebody when they’re struggling, not only because they need health care, but also because I’m able to understand them based on our culture,” she said, “and I love that.”

Afzal is amazed by the breadth of her clinical rotations at Kaiser Permanente. One of her physician mentors allowed her to place an umbilical vein catheter into a newborn, a procedure more commonly offered to an experienced resident.

The director of medical education for Kaiser Permanente Central Valley, Howard Young, said the partnership with UC Davis is successful because of the common values held by both organizations.

“UC Davis and Kaiser Permanente share very similar missions and visions of not just serving our communities but also helping improve the health of our communities.”

He added: “And what better way of doing that than by sharing our collective educational knowledge and educational learning experiences to create an incredible learning environment for our students.”